Haiti is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea. Hispaniola has two countries. Haiti makes up roughly the western 1/3 of the island. The Dominican Republic makes up the eastern 2/3 of the island. The two countries are not on very friendly terms and never have been. Their roots are very different. Haiti is primarily populated by African-Caribbean people with a history of French colonialism. The Dominican Republic is made up of Afro-European mixed blooded people and their roots are deeply influenced by Spanish colonialism.

Additionally the two countries have a long history of mistrust, even hatred. Haiti has twice occupied The Dominican Republic in the 19th century, and in 1937 The Dominican Republic perpetrated a terrible massacre on Haitians living in or near The Dominican Republic's borders.

Haiti is about the size of the U.S. state of Maryland, just over 10,000 square miles. The current population is roughly 7,500,000 in Haiti. Another million Haitians are living abroad in the U.S., Canada and France. It is difficult to know how many of these people are simply waiting for conditions to improve in Haiti, or to what extent these Haitians living abroad are now becoming residents and citizens in these host nations.

From 1957 to 1986 Haiti was ruled by the Duvalier family in the persons of Francois Duvalier (Papa Doc -- 1957-1971) and his son, Jean-Claude Duvalier (Baby Doc -- 1971-1986). This was a period of brutal dictatorship, the suppression of most normal freedoms in Haiti, particularly political dissent from the "Duvalier revolution." It was, also, in the later years, a period of a rather stable law and order society that one tends to get with dictatorships.

In 1986 there was an uprising of the people of Haiti and president Jean-Claude Duvalier fled Haiti. At this time Haiti entered into a very difficult period which is still going on. It is a period of struggle for control of the country, and what has resulted is a great deal of political and social instability. There seem to be a number of factions including:

Old line Duvalierists trying to keep change from coming to Haiti.

New line populists, most commonly associated with former president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide and the current president, Rene Preval.

There seems to be another force that has entered into the fray which is not quite in the Duvalierist camp, but is also opposed to most of the reforms intended by the populists. These are the drug lords and younger army officers, not fully integrated into the old guard Duvalierists world.

Today Haiti is a nation in disarray and disorder, unsafe, economically desperate without much clear hope of significant improvement in the very near future. It is a country in struggle.

The vast majority of Haiti's people live in desperate poverty and personal unsafety. They are jobless, hungry, unsafe and discouraged. Despite this many continue to struggle for populist reform. These masses are without much power other than their sheer numbers. The opposition has power, money and most importantly, weapons.

The international community, especially the United States, which has great power in Haiti, seems without serious interest in the plight of the masses of the Haitian poor.

THE PRE-COLUMBIAN PERIOD.

Before Columbus landed on the island (Dec. 6, 1492), his second land-fall in the "New World," there was a large population of Taino/Arawak people who lived on the island in relative peace. It's difficult to know their numbers with any exactitude, but somewhere over 1/2 million seems a reasonable estimate.

They lived lives of great simplicity, farming and fishing. There was little native game on the island to supplement their diets. They had few enemies, but seem to have feared the more war-like and aggressive Carib people who were centered on the nearby island that is today Puerto Rico.

Unfortunately for the Taino/Arawak, they befriended the Spanish, and gave them some gifts of gold jewelry. There wasn't much gold on Hispaniola, but the Spanish assumed otherwise and thought that Hispaniola was to be the motherload of gold they hoped to find. This led to return voyages to the island and the suppression of the Taino/Arawak.

It soon became clear that there wasn't much gold on Hispaniola, and the Spanish turned it into a bread basket, providing food for the conquistadors who were exploring and conquering peoples in the rest of the Caribbean and Central America. In the process the Taino/Arawak were virtually enslaved.

They did not respond well to this new state of slavery. They died in the labor and more than that they died from European diseases. Effectively, as a distinct and recognizable people on the island of Hispaniola, they disappeared by the middle of the 17th century. The Taino/Arawak survived in other areas of the Caribbean and South America, but not on Hispaniola.

Other than in this historical context, they don't contribute much to the later development of the country of Haiti. Their labor was supplanted by African slaves (the ultimate root of the people who today make up the population of Haiti). Certainly there must have been some inter-mating between members of the two peoples, thus some remnants of Taino/Arawak blood must have been passed on, and there are a few words of language or a custom here and there that MIGHT be traced back to a Taino/Arawak influence. However, this blood and cultural contribution is quite negligible in the formation of the Haitian people.

SPANISH COLONIALISM: SUGAR AND SLAVES

The Spanish quickly saw that Hispaniola was not to be the source of gold for Spain. Hispaniola was converted into a farming region to provide food for the Spanish in other areas of the Caribbean and Central American. The island was worked first by the Taino/Arawak, but before long, African slaves were imported. This began as early as 1508 and the Africans became the primary labor source very quickly. Sugar was introduced as a crop to join tobacco and coffee as attractive crops as well as regular food stuffs.

However, before long Hispaniola became an island of little interest to the Spanish. Spanish settlements were being founded in other areas of the Caribbean and Central and South America and these settlers found it more economical to provide their own food. Hispaniola became a quite uninteresting and useless island. There was one town at the far southeast portion of the island, the settlement which is today the capital of the Dominican Republic, Santo Domingo. The Spanish kept this settlement and the farms around it, but little by little the rest of the island was virtually abandoned and unpopulated (including the extremely fertile western part of the island which was later to become Haiti).

PIRATES AND THE FRENCH SETTLEMENT IN THE WEST

In the 17th and century the major nations of Europe sponsored privateers. These were basically free-lance sailors who worked for a European nation and harassed the shipping of rival nations. The sailors or freebooters as they were called, often received a portion of the spoils won in these high seas battles and were the forerunners of the later pirates.

When the nations of Europe de-emphasized the use of privateers, there was a large navy of these tough folks who were not ready to give up their lives of high-seas raiding. They became non-governmental free lance robbers, the pirates that we all know of.

One of the strong holds for the pirates was the island of La Tortue (Turtle Island), a small island, just a few miles off the northern coast of what is today Haiti, and, today, a possession of Haiti. The dominant group of pirates who used La Tortue as their base were French pirates.

From the Spanish days of using the western portion of the island, 50 to 100 years earlier, there were many wild animals which survived after the Spanish gave up the use of the island. This included cattle, goats, sheep and horses. Since this region, the northern plain and mountains of Haiti, was very fertile, the animals flourished. The pirates were fond of going across the narrow water way into the island of Hispaniola to hunt wild game.

They used to kill the game and cook it over an open flame. This is a "boukan" in French, and this process and these people became known as "boukanniers" in French, or buccaneers in English, a common term for pirates.

However, pirating wasn't what it used to be and some of these French pirates choose to settle in Hispaniola and become farmers. They sent back to France for women, and France was only too happy to empty some of the women's prisons, sending a variety of women not desired in France, to this remote Caribbean outpost. Slowly a community developed in the northcentral and northwest of Hispaniola. By the early part of the 17th century the French even named some of these former pirates as French officials to oversee the community forming there.

The Spanish protested the French presence, but never really pushed it too much. The community waxed and crops began to flow back to France. It was an attractive place, fertile and with great potential as a colony.

Finally, in 1697 at the Treaty of Rystwik, at the conclusion of a European war not involving Hispaniola at all, the Spanish needed another bargaining chip and ceded the western portion of Hispaniola to the French. Thus the island was divided. The eastern Spanish portion was called Santo Domingo, Spanish for St. Dominic. The western French portion was called San Domingue, French for St. Dominic. But the island was now divided and a defining characteristic, the geographic one, was fixed for modern day Haiti.

THE FRENCH COLONIAL PERIOD

From the official birth of the colony of San Domingue (1697) for just over 100 years, the French colony waxed and became one of the richest colonies in the history of the world.

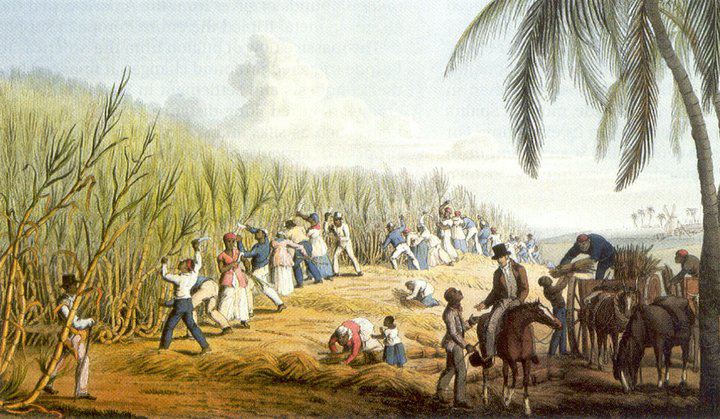

An agricultural economy based on slave labor grew sugar cane, coffee, the dye indigo, cotton, tobacco and many exotic spices which were in high demand in Europe and Asia. The planters produced the goods but were prohibited from processing the crops in the colony itself. Thus all the goods were shipped to France and processed there. From the processing plants French merchants spread out to the whole of Europe and near-Asia creating a booming economy for France. Another huge portion of this economy was the slave trade itself.

The French colonial slave system was particularly brutal, worse that virtually any other place in the Western world. Slaves were routinely treated with great brutality and inhumanity. However, the French foolishly, for their own safety, allowed the number of slaves to grow without any concern and within a 100 years of colonial rule had arrived at a very dangerous 10-1 ratio of free to slave population. In 1791 there were approximately 500,000 slaves and about 50,000 free people. Some 30,000 of those free people were people of color, both black and mulatto.

In the French colonial system free people of color could own slaves and property, however there were other restrictions. On San Domingue the free people of color were not much into the sugar trade but mainly controlled coffee. However they were a distinct "ruler" class.

This structure was phenomenally determinative of much of later Haitian history. After independence and the coming of a black republic, this class of former free planters emerged as rulers of Haiti. This class structure of a very small class of rulers and a huge mass of common folks has always been the norm in Haiti and is one of the greatest barriers to the emergence of Haiti into a nation with any serious sense of democratic equality.

THE HAITIAN REVOLUTION: 1791-1804.

The spirit of the French Revolution infected Haiti. Added to that the brutality of the French slave system and the huge number of slaves in relation to the free people and the stage was set for a lasting revolution. There had been many revolts of slaves and attempts and social change, but the final moment of French rule came in Aug. 1791 with an uprising which was more about the rights of free people of color than freedom for slaves.

Nonetheless, this 1791 uprising developed into a full-fledged revolution war. France realized the crucial economic importance of the colony and made every attempt to defend their rule. Eventually it came down to Napoleon sending a large expeditionary force to win the colony back securely for France in 1802. This caused the last eruption of revolutionary fervor and the defeat of the French. On Jan. 1, 1804 the nation of Haiti was proclaimed. It was an all-black (and mulatto) republic with a constitutional prohibition against white people owning land. This particular provision of the Haitian constitution lasted until 1918 until the occupying forces of the United States forced a constitution onto Haiti which did not contain this prohibition.

There is much controversy about the Haitian Revolution and what sense to make of this victory over the French. We will study this in much greater detail in due time.

EARLY DAYS OF INDEPENDENCE: IMITATING THE FRENCH MODEL

The fledging leaders of the newly independent Haiti, Dessalines and Christophe, attempted to imitate the French system without slavery. They wanted to build an economy based on plantation agriculture and sugar. Actually they made astonishing achievements, both returning the economy to roughly 75% of the productivity of the pre-Revolutionary period. However, this was done within the context of a social system which while not a slave economy, approached it, looking much more like European serfdom. This was simply not what the Haitian people wanted.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE "TWO HAITIS"

Between about 1820 to 1840, under the presidencies of Alexander Petion and Jean-Pierre Boyer, the old French plantation system of economy died forever.

In the briefest form what developed was a world of one nation, but really two Haitis. There was the official nation of Haiti, ruled by the government, but really centered in the two main cities, Port-au-Prince and Cap Haitien and the next half-dozen largest towns, all but one being a seaport town. (The sole exception was the inland Central Plateau town of Hinche.)

These towns were controlled by the small property owning elite. The vast majority of Haitian people lived in the rural areas and basically didn't belong to "Haiti" in any normal sense of the term. The did subsistence agriculture and stayed away from "Haiti" and its government and army as much as they possibly could. Given the mountainous nature of much of Haiti this was not difficult to achieve. There were buffer zones, markets, where the rural peasants could trade agricultural products, especially coffee, at a fraction of its international value, in exchange for essentials. This trade allowed the elite class to make a substantial income and for the masses of people to survive in some sort of peace, security and isolation from "Haiti," the official nation.

Again, this process was extremely definitive in forming and creating the fundamental social, economic and governmental system which is still dominant in Haiti today.

THE IMPACT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY: HAITIAN INDEPENDENCE THROUGH THE U.S. OCCUPATION OF 1915.

The white slave owning world was utterly shocked by the victory of Haitian revolutionaries over France. Here was a white world with slaves (England didn't banish slavery in 1833, the first major white nation to do so, and the U.S. held slaves until 1862) and this was a terrifying situation. There was much talk of "servile revolutions" and the worry was that slaves in other places would take the successful Haitian revolutionaries as models and revolt in other locations. This was a special worry in the south of the United States where the agricultura; economies of cotton and tobacco were completely slave-dependent.

In France there was the further concern for the usurped property of French citizens, the former white planters from San Domingue. The French wanted recompense for this property before it would recognize Haitian independence.

Further there were a great outcry in the white world that black people were inherently incapable of ruling themselves. Multitudes of books and pamphlets belabored this view in the early 19th century and Haiti always came in for attack as one of the key pieces of evidence of this impossibility.

It is important to note that the success of the Haitian Revolution came just at the same time as the French and American Revolutions. This was the period of the birth of functional democracy.

But, the white nations of Europe and the United States refused to recognize Haitian independence and boycotted trade relations with Haiti. This was one of the major causes of the development of the "two Haitis" that I discussed above, and made the growth of democracy in Haiti to be virtually impossible.

The masses of Haitian rural peasants were illiterate and remain so today. Both the Industrial Revolution and the Democratic Revolutions passed Haiti by.

It is critically important to understand the causal implications of these actions and attitudes of the outside world on the internal development of the history of Haiti.

FROM THE 1840S TO THE U.S. OCCUPATION OF 1915.

Within Haiti there began a curious and disastrous series of governmental revolutions. Basically the government was a tiny class of elite. Various factions of the elite would sponsor a "president" and under the protection of this particular government the favored faction of the elite would pillage the Haitian treasury. After a certain amount of time a different faction of the elite, normally funded by foreign (often German) capital, would raise an army, march on Port-au-Prince and drive the sitting government into exile. The new faction would take its turn at the troff of the Haitian treasury and the cycle continued.

The upshot of this period of Haitian history is critical. First of all it further established the class and color relations which exist to this very day as dominant patterns in Haitian life. Further, the role of foreign capital in funding these revolutions gave an increasing foothold of foreign capital. This became troubling to the United States after the decision to build the Panama Canal. This geo-political decision of the U.S. gave rise to a much more militant interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine and desire for full control over the Caribbean, the "back yard" of the U.S. As World War I approached, the penetration of German capital into Haiti was a great worry to the U.S.

Using a trumped up concern for U.S. financial interests and the "concern" with approaching anarchy in Haiti, the U.S. occupied Haiti in June 1915 and remained in control of Haiti until 1934, with financial and political hegemony continuing long after the end of the official occupation. In many ways it still continues today.

From 1915 until and including the present, the United States has been a major power and factor in what does and does not happen in Haiti.

THE WINDS OF CHANGE: NOIRISM (NEGRITUDE MOVEMENT) IN HAITI DURING THE AMERICAN OCCUPATION.

In the 1930s a movement sprang up in Haiti which turned the mainly mulatto intellectual class away from its old power base -- imitation of white, French European models of life and meaning -- and toward a greater appreciation of blackness, Africanness and Haiti's roots in the common black people.

This movement effected the intellectual class, especially poets, novelists and other writers first, later on artists as well. It set the stage for a political ideology which led the "black revolution" which Francois Duvalier (Papa Doc) was pledging to enact before it got sidetracked into the personalist dictatorship of the Duvalier dynasty.

HAITI'S DESPERATE POVERTY AND THE 1986 REVOLUTION.

Haiti's peasants may have lived lives of agrarian simplicity in order to escape a corrupt and damaging government, but eventually simplicity gave way to misery. It's hard to fix when this occurred, but the dynamics are not too hard to see.

Haitian peasants owned a bit of land. However, they chose to divide the land equally among their sons. Thus land plot sizes got smaller and smaller as the population grew. Secondly, the peasants used farming methods which we actually harmful to the land, burning off top soil, and over-planting crops which took too much out of the soil. Lastly, since the only fuel in the country is wood, little by little the vast forests of Haiti were cut, overwhelmingly for charcoal. The land became deforested and the soil could not hold against the season torrential rains. The top soil of Haiti washed away into the sea leaving great pressure on the land left. The result was eventually misery. My own suspicion is that agrarian simplicity with a modestly adequate diet became increasingly scarce after the beginning of the 20th century, and now, as that century ends, Haiti is left in a desperate situation in which millions of her people are malnourished, hungry and having little hope or prospects for a better future.

However, a populist movement somewhat tied to the democratic impetus implicit in Latin American Liberation Theology arose in Haiti in the late 1970s and gained power in the early 1980s. On February 7, 1986 this movement culminated with the fleeing of Jean-Claude Duvalier to France on an U.S. military jet. There was a great deal of hope in the latter part of the 80s, but since then things have deteriorated and today the Haitian movement for more populist movement is in great struggle with forces of reaction.

THE RISE OF ARISTIDE (1990–91)

In December 1990, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a liberation theology Roman Catholic (Salesian) priest, won 67% of the vote in elections that international observers deemed largely free and fair.

Aristide's radical populist policies and the violence of his bands of supporters alarmed many of the country's elite, and, in September 1991, he was overthrown in the 1991 Haitian coup d'état, which brought General Raoul Cédras to power. The coup saw hundreds killed, and Aristide was forced into exile, his life saved by international diplomatic intervention.

MILITARY RULE (1991–94)

An estimated 3 000–5 000 Haitians were killed during the period of military rule. The coup created a large-scale exodus of refugees to the United States. The United States Coast Guard interdicted (in many cases, rescued) a total of 41 342 Haitians during 1991 and 1992. Most were denied entry to the United States and repatriated back to Haiti. According to Mark Weisbrot, Aristide has accused the United States of backing the 1991 coup. In response to the coup, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 841 imposing international sanctions and an arms embargo on Haiti.

On 16 February 1993, the ferry Neptune sank, drowning an estimated 700 passengers. This was the worst ferry disaster in Haitian history.

The military regime governed Haiti until 1994, and according to some sources included drug trafficking led by Chief of National Police Michel François. Various initiatives to end the political crisis through the peaceful restoration of the constitutionally elected government failed. In July 1994, as repression mounted in Haiti and a civilian human rights monitoring mission was expelled from the country, the United Nations Security Council adopted United Nations Security Council Resolution 940, which authorized member states to use all necessary means to facilitate the departure of Haiti's military leadership and to restore Haiti's constitutionally elected government to power.

THE RETURN OF ARISTIDE (1994–96)

In mid-September 1994, with U.S. troops prepared to enter Haiti by force for Operation Uphold Democracy, President Bill Clinton dispatched a negotiating team led by former President Jimmy Carter to persuade the authorities to step aside and allow for the return of constitutional rule. With intervening troops already airborne, Cédras and other top leaders agreed to step down. In October, Aristide was able to return. The Haitian general election, 1995 in June 1995 saw Aristide's coalition, the Lavalas (Waterfall) Political Organization, gain a sweeping victory, and René Préval, a prominent Aristide political ally, elected President with 88% of the vote. When Aristide's term ended in February 1996, this was Haiti's first ever transition between two democratically elected presidents.

PREVAL'S FIRST PRESIDENCY (1996–2001)

In late 1996, Aristide broke with Préval and formed a new political party, the Lavalas Family (Fanmi Lavalas, FL), which won elections in April 1997 for one-third of the Senate and local assemblies, but these results were not accepted by the government. The split between Aristide and Préval produced a dangerous political deadlock, and the government was unable to organize the local and parliamentary elections due in late 1998. In January 1999, Préval dismissed legislators whose terms had expired – the entire Chamber of Deputies and all but nine members of the Senate, and Préval then ruled by decree.

ARISTIDE'S SECOND PRESIDENCY (2001–04)

In May 2000 the Haitian legislative election, 2000 for the Chamber of Deputies and two-thirds of the Senate took place. The election drew a voter turnout of more than 60%, and the FL won a virtual sweep. However, the elections were marred by controversy in the Senate race over the calculation of whether Senate candidates had achieved the majority required to avoid a run-off election (in Haiti, seats where no candidate wins an absolute majority of votes cast has to enter a second-round run-off election). The validity of the Electoral Council's post-ballot calculations of whether a majority had been attained was disputed. The Organization of American States complained about the calculation and declined to observe the July run-off elections. The opposition parties, regrouped in the Democratic Convergence (Convergence Démocratique, CD), demanded that the elections be annulled, and that Préval stand down and be replaced by a provisional government. In the meantime, the opposition announced it would boycott the November presidential and senatorial elections. Haiti's main aid donors threatened to cut off aid. At the November 2000 elections, boycotted by the opposition, Aristide was again elected president, with more than 90% of the vote, on a turnout of around 50% according to international observers. The opposition refused to accept the result or to recognize Aristide as president.

Allegations emerged of drug trafficking reaching into the upper echelons of government, as it had done under the military regimes of the 1980s and early 1990s (illegal drug trade in Haiti). Canadian police arrested Oriel Jean, Aristide's security chief and one of his most trusted friends, for money laundering. Beaudoin Ketant, a notorious international drug trafficker, Aristide's close partner, and his daughter's godfather, claimed that Aristide "turned the country into a narco-country; it's a one-man show; you either pay (Aristide) or you die".

Aristide spent years negotiating with the Convergence Démocratique on new elections, but the Convergence's inability to develop a sufficient electoral base made elections unattractive, and it rejected every deal offered, preferring to call for a US invasion to topple Aristide.

THE 2004 COUP D'ÉTAT

Anti-Aristide protests in January 2004 led to violent clashes in Port-au-Prince, causing several deaths. In February, a revolt broke out in the city of Gonaïves, which was soon under rebel control. The rebellion then began to spread, and Cap-Haïtien, Haiti's second-largest city, was captured. A mediation team of diplomats presented a plan to reduce Aristide's power while allowing him to remain in office until the end of his constitutional term. Although Aristide accepted the plan, it was rejected by the opposition, which mostly consisted of Haitian businessmen and former members of the army (who sought to reinstate the military following Aristide's disbandment of it).

On 29 February 2004, with rebel contingents marching towards Port-au-Prince, Aristide departed from Haiti. Aristide insists that he was essentially kidnapped by the U.S., while the U.S. State Department maintains that he resigned from office. Aristide and his wife left Haiti on an American airplane, escorted by American diplomats and military personnel, and were flown directly to Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic, where he stayed for the following two weeks, before seeking asylum in a less remote location. This event was later characterized by Aristide as a kidnapping.

Though this has never been proven, many observers in the press and academia believe that the US has not provided convincing answers to several of the more suspicious details surrounding the coup, such as the circumstances under which the US obtained Aristide's purported letter of "resignation" (as presented by the US) which, translated from Kreyòl, may not have actually read as a resignation.

Aristide has accused the U.S. of deposing him in concert with the Haitian opposition. In a 2006 interview, he said the U.S. went back on their word regarding compromises he made with them over privatization of enterprises to ensure that part of the profits would go to the Haitian people and then "relied on a disinformation campaign" to discredit him.

Political organizations and writers, as well as Aristide himself, have suggested that the rebellion was in fact a foreign controlled coup d'état. Caricom, which had been backing the peace deal, accused the United States, France, and the International community of failing in Haiti because they allegedly allowed a controversially elected leader to be violently forced out of office. The international community stated that the crisis was of Aristide's making and that he was not acting in the best interests of his country. They have argued that his removal was necessary for future stability in the island nation.

Some investigators claimed to have discovered extensive embezzlement, corruption, and money laundering by Aristide. It was claimed Aristide had stolen tens of millions of dollars from the country, though specific bank account documents proving this have yet to be presented. None of the allegations about Aristide's involvement in embezzlement, corruption, or money laundering schemes could be proven. The criminal court case brought against Aristide was quietly shelved, though various members of his Lavalas party languished for years in prison without charge or trial due to similar accusations. The Haitian government suspended the suit against Aristide on 30 Jun 2006 to prevent it from being thrown out for want of prosecution.

The government was taken over by Supreme Court Chief Justice Boniface Alexandre. Alexandre petitioned the United Nations Security Council for the intervention of an international peacekeeping force. The Security Council passed a resolution the same day "taking note of the resignation of Jean-Bertrand Aristide as President of Haiti and the swearing-in of President Boniface Alexandre as the acting President of Haiti in accordance with the Constitution of Haiti" and authorized such a mission. As a vanguard of the official U.N. force, a force of about 1,000 U.S. Marines arrived in Haiti within the day, and Canadian and French troops arrived the next morning; the United Nations indicated it would send a team to assess the situation within days. These international troops have been criticized for cooperating with rebel forces, refusing to disarm them, and integrating former military and death-squad (FRAPH) members into the re-militarized Haitian National Police force following the coup.

On 1 June 2004, the peacekeeping mission was passed to MINUSTAH and comprised a 7,000 strength force led by Brazil and backed by Argentina, Chile, Jordan, Morocco, Nepal, Peru, Philippines, Spain, Sri Lanka, and Uruguay.

Brazilian forces led the United Nations peacekeeping troops in Haiti composed of United States, France, Canada, and Chile deployments. These peacekeeping troops were a part of the ongoing MINUSTAH operation.

In November 2004, the University of Miami School of Law carried out a Human Rights Investigation in Haiti and documented serious human rights abuses. It stated that "summary executions are a police tactic."[61] It also suggested a "disturbing pattern."

On 15 October 2005, Brazil called for more troops to be sent due to the worsening situation in the country.

After Aristide's overthrow, the violence in Haiti continued, despite the presence of peacekeepers. Clashes between police and Fanmi Lavalas supporters were common, and peacekeeping forces were accused of conducting a massacre against the residents of Cité Soleil in July 2005. Several of the protests resulted in violence and deaths.

THE SECOND PRÉVAL PRESIDENCY (2006–2011)

In the midst of the ongoing controversy and violence, however, the interim government planned legislative and executive elections. After being postponed several times, these were held in February 2006. The elections were won by René Préval, who had a strong following among the poor, with 51% of the votes. Préval took office in May 2006.

In the spring of 2008, Haitians demonstrated against rising food prices. In some instances, the few main roads on the island were blocked with burning tires and the airport at Port-au-Prince was closed. Protests and demonstrations by Fanmi Lavalas continued in 2009.

EARTHQUAKE 2010

On 12 January 2010, Haiti suffered a devastating earthquake, magnitude 7.0 with a death toll estimated by the Haitian government at over 300,000, and by non-Haitian sources from 50,000 to 220,000. Aftershocks followed, including one of magnitude 5.9. The capital city, Port-au-Prince, was effectively leveled. A million Haitians were left homeless, and hundreds of thousands starved. The earthquake caused massive devastation, with most buildings crumbled, including Haiti's presidential palace. The enormous death toll made it necessary to bury the dead in mass graves. Most bodies were unidentified and few pictures were taken, making it impossible for families to identify their loved ones. The spread of disease was a major secondary disaster. Many survivors were treated for injuries in emergency makeshift hospitals, but many more died of gangrene, malnutrition, and infectious diseases.

THE MARTELLY PRESIDENCY (2011–2016)

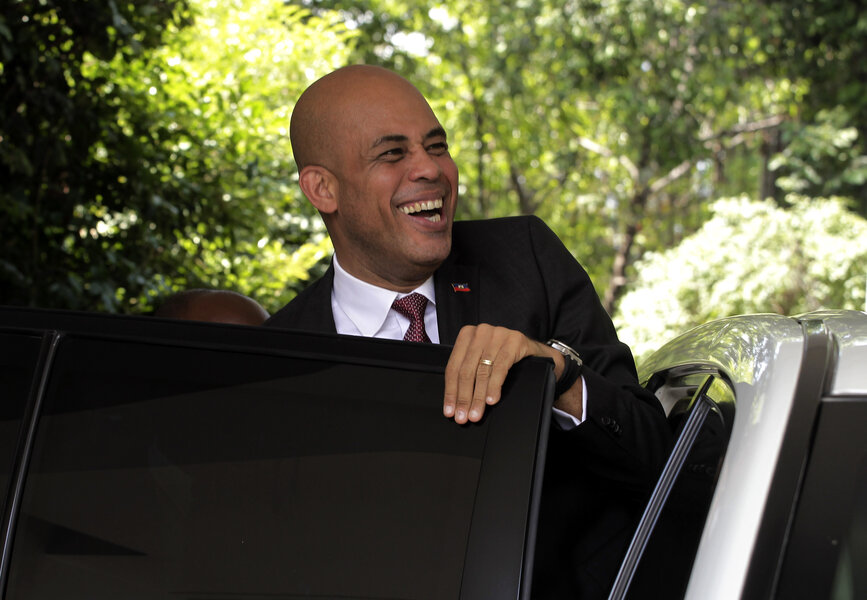

On 4 April 2011, a senior Haitian official announced that Michel Martelly had won the second round of the election against candidate Mirlande Manigat. Michel Martelly also known by his stage name "Sweet Micky" is a former musician and businessman. On 8 February 2016, Michel Martelly stepped down at the end of his term without a successor in place.